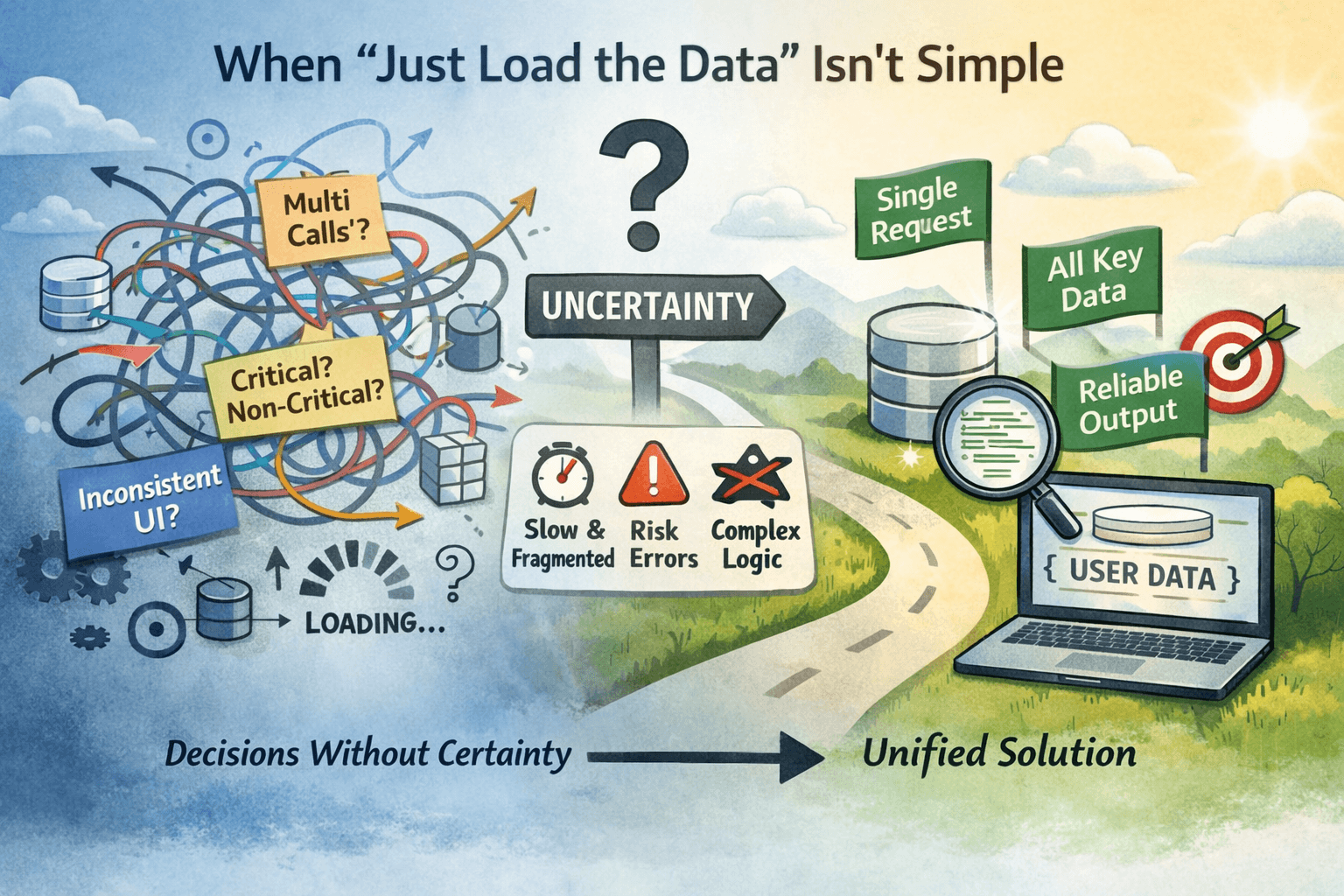

When “Just Load the Data” Isn’t Simple: Making Decisions Under Uncertainty in Initial App Load

How we eliminated UI flicker and reduced load time in a Telegram Mini App by loading all user data in a single PostgreSQL query.

We were working on a mental health support app for men, delivered as a Telegram Mini App.

From a product perspective, the requirement was straightforward: on first launch, the user should immediately see the correct screen, in the correct language, with the correct state.

From an engineering perspective, this turned out to be a problem of coordinating data under real constraints.

The app itself is a React + TypeScript SPA.

The backend is built on Supabase, using PostgreSQL and Supabase Edge Functions.

Authentication is handled via Telegram WebApp init data.

You can see the app here:

👉 https://t.me/menhausen_app_bot/app

1. The Actual Problem We Faced

On the very first load (no local cache), the UI was rendered before user data was fully available.

This led to a set of issues that were immediately visible to users:

- brief display of the wrong screen

- incorrect language before preferences loaded

- onboarding or survey screens flashing and then disappearing

- UI state changing after the first render

Technically, the root cause was simple:

user data was split across ~10 API calls, each responsible for its own slice of state.

Those calls were:

- sequential in some cases

- parallel in others

- dependent on authentication timing

- subject to network latency and edge execution time

End result: ~2–3 seconds before the app actually knew who the user was.

2. Why Partial Loading Didn’t Work Here

We initially tried to reason in terms of critical vs non-critical data.

That approach failed quickly.

In this app:

- onboarding state affects routing

- language affects text rendering

- subscription status affects available flows

- progress and check-ins affect the first visible screen

In practice, almost all user data influenced the first render.

Trying to load “just enough” data introduced:

- additional code paths

- race conditions between “fast” and “full” sync

- UI churn after render

At that point, the problem wasn’t performance – it was state correctness.

3. The Key Decision: Aggregate at the Database

Instead of trying to orchestrate many requests at the application level, we moved aggregation into PostgreSQL.

The idea was simple:

- fetch all user-related data in one request

- return it as a single serialized JSON object

- block UI rendering until that data is available

At the core of this approach is a PostgreSQL function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION get_user_data_as_json(p_user_id BIGINT)

RETURNS JSON AS $$

DECLARE

result JSON;

BEGIN

-- aggregation logic

result = json_build_object(

'user', json_build_object(

'id', p_user_id,

'name', 'John Doe'

)

);

RETURN result;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql STABLE;

Inside the function, data from multiple tables is aggregated using:

json_build_objectjson_aggjson_object_aggexplicit

COALESCEhandling for empty arrays and nulls

From a database perspective, this turned out to be very fast.

Data aggregation itself consistently took ~4–40 ms.

4. Where the Time Actually Went

An important observation: the PostgreSQL function execution was not the bottleneck.

Most of the remaining latency came from:

Supabase Edge Function startup

network overhead between client → edge → database

Even with that overhead, the total time dropped dramatically because:

we removed ~9 extra round trips

serialization happened once, close to the data

the client received a ready-to-use JSON payload

Instead of coordinating 10 responses, the app now waits for one.

5. Client-Side Flow After the Change

The client logic became intentionally boring:

Authenticate via Telegram WebApp data

Call a single Edge Function

Receive full user state as JSON

Render the first screen

No background sync. No “fast critical data” path. No UI reconciliation after render.

If the new RPC-based path fails, the system falls back to the legacy multi-request flow. This fallback was kept deliberately to reduce migration risk.

6. Trade-offs We Accepted Explicitly

This approach is not free.

What we gained:

- initial load time dropped from ~2–3 seconds to ~300 ms

- no UI flicker

- correct screen and language on first render

- dramatically simpler client logic

What we accepted:

- more logic inside PostgreSQL

- schema changes require updating the function

- we always load more data than strictly necessary

- the fallback path must remain tested and working

For this application size and domain, that trade-off was acceptable.

7. What This Reinforced for Us

A few practical lessons stood out:

- PostgreSQL is extremely good at JSON aggregation when used intentionally

- Fewer requests often matter more than faster individual requests

- Blocking render until state is correct can improve perceived performance

- Edge function overhead can dominate latency once database work is optimized

- Explicit null and empty-state handling is critical for new users

Most importantly: simplifying the data-loading model reduced both bugs and cognitive load.

Conclusion

This was not about discovering a clever trick. It was about aligning the data-loading strategy with how the UI actually depends on state.

By moving aggregation into PostgreSQL and switching from ~10 API calls to one serialized JSON response, we made the system faster, more predictable, and easier to reason about.

For apps where the first screen depends on many intertwined pieces of user state, “load everything, then render” can be the simplest and safest choice.

This is not a universal pattern. But in this case, it matched the reality of the product better than any partial solution ever did.

Comments powered by Disqus.